Replacing Damaged ‘Hair’ Cells May Help Treat Hearing Loss

Inside a bony structure that spirals like a snail shell in a human’s inner ear, roughly 15,000 “hair” cells receive, translate, and then ship sound signals to the brain. Damage to these cells from excessive noise, chronic infections, antibiotics, certain drugs, or the simple passing of time can lead to irreparable hearing loss.

Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI) researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) and Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary and colleagues from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have developed an approach to replace damaged sound-sensing hair cells, which eventually may lead to therapies for people who live with disabling hearing loss.

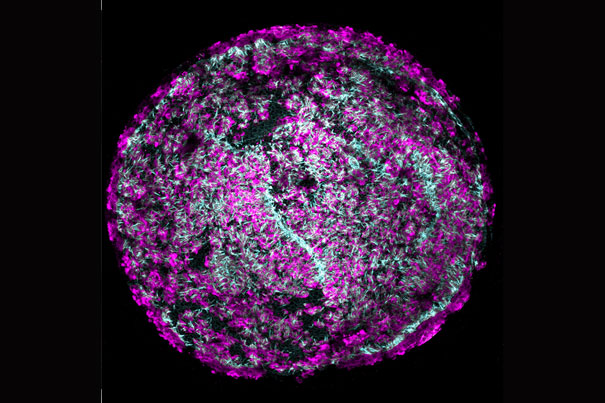

In a recent Cell Reports study, the researchers identified a small molecule cocktail that increased the population of cells responsible for generating hair cells in the inner ear. Unlike hair on the human head, the hair cells lining that bony structure, called the cochlea, do not regenerate.

HSCI principal faculty Jeff Karp, HSCI affiliate faculty Albert Edge, and MIT’s Robert Langer were co-corresponding authors of the study. Will McLean, a postdoctoral fellow in the Edge lab, and Xiaolei Yin, an instructor in medicine at BWH, were co-first authors.

In 2012, Edge and colleagues identified a population of stem cells, characterized by an Lgr5+ marker, which scientists could turn into hair cells in a dish. A year later, Edge had converted the resident population of these cells in mice into hair cells, though the ability to restore hearing using this approach has been limited.

“The problem is the cochlea is so small and there are so few cells” that it creates a bottleneck limiting the number and types of experiments researchers could perform, said Edge, director of the Tillotson Cell Biology Unit at Mass. Eye and Ear and a professor of otolaryngology at Harvard Medical School (HMS).

However, by exposing Lgr5+ cells isolated from the cochlea of mice to the small molecule cocktail, the researchers were able to create a 2,000-fold increase in the number of stem cells.

“Those molecules were a key to unlocking this regenerative capability,” said Karp, who is also a bioengineer at BWH and an associate professor of medicine at HMS.

Inspired by creatures with significant regenerative potential, including lizards and sharks, Karp’s lab initially turned to one of the body’s most highly regenerative tissues, the gastrointestinal lining, which completely replaces itself every four to five days. Central to this process is the paneth cell, neighbor to the intestinal stem cells that are responsible for generating all mature cell types in the intestine. The paneth cells effectively tell the stem cells, also characterized by their Lgr5+ markers, when to turn on and off.

Karp and his colleagues at MIT looked at the basic biology of the ties between paneth cells and intestinal stem cells and identified small molecules that could communicate directly with and control the Lgr5+ stem cells.

“While we were developing the approach for the intestinal cells, we demonstrated it also worked in several other tissues with the Lgr5+ stem cells and progenitors, including the inner ear,” Karp said.

When the researchers coupled the cocktail with established differentiation protocols, they were able to generate large quantities of functional hair cells in a petri dish. Using protocols from the Edge lab, the researchers then thoroughly characterized the differentiated cells to demonstrate they were functional hair cells. Researchers tested the cocktail on newborn mice, adult mice, non-human primates, and cells from a human cochlea.

“We can now use these cells for drug screening as well as genetic analysis,” Edge said. “Our lab is using the cells to better understand the pathways for expansion and differentiation of the cells.”

Additionally, the small molecule cocktail may also be turned into a therapeutic treatment. Karp has co-founded Frequency Therapeutics, which plans to use insights from these studies to develop treatments for hearing loss. The team hopes to begin human clinical testing within 18 months.

“Not only is it a potential therapeutic that could be relevant for the restoration of hearing, but this approach is a platform,” said Karp. “The concept of targeting stem cells and progenitor cells in the body with small molecules to promote tissue regeneration can be applied to many tissues and organ systems.”

Source: Harvard News

“Replacing damaged ‘hair’ cells may help treat hearing loss” by:Hannah L. Robbins